Things to Do in Bali

Beautiful and Meaningful

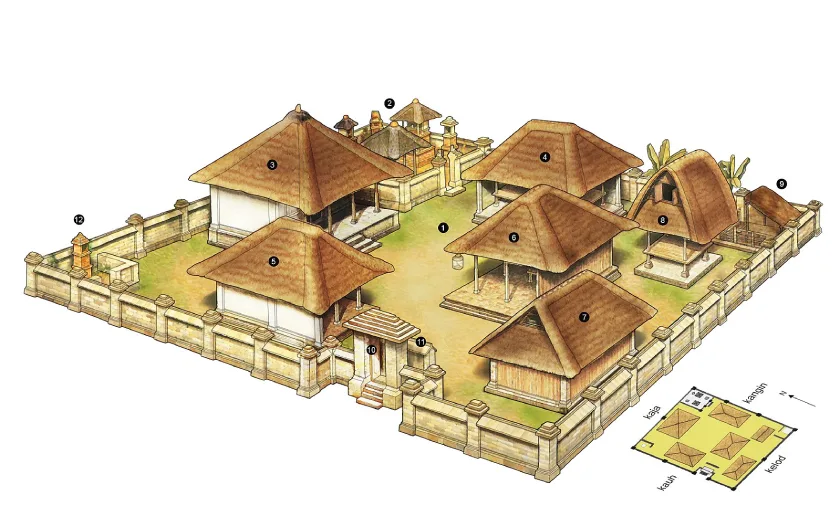

When you visit Bali, you’ll notice the distinctive architecture that defines the island’s homes, temples, and community spaces. As you explore Ubud’s family-run guest houses, wander through traditional villages, or perhaps have the chance to visit a Balinese family’s home, you’ll see how each compound is laid out with purpose, reflecting deep cultural values and community guideliens.

The homes are not just residences but sacred spaces—each element from the family temple to the open-air pavilions is arranged to respect the balance of natural and spiritual forces.

Balinese Traditional Architecture

Balinese architecture is an art form rooted in centuries-old Hindu beliefs, where buildings are meticulously designed to create harmonious and spiritually balanced spaces. Traditional Balinese houses, palaces, and temples are built within a compound (pekarangan), which includes multiple structures dedicated to distinct functions, from religious worship to family gatherings.

Sacred Principles of Balinese Architecture

The layout and design of buildings adhere to Asta Kosala Kosali, a traditional architectural philosophy similar to the principles of feng shui. This Balinese system ensures each building aligns with natural forces to maintain a harmonious energy flow. Notably, all structures must honor the direction kaja (toward the mountains), which is considered the most sacred direction, while kelod (toward the sea) symbolizes impurity.

For the Balinese, the art of building is therefore guided by ancient principles and preserved knowledge. Master builders (undagi) and priests ensure that buildings follow the rules of asta kosala kosali, in order to create spaces that honor and maintain harmony with Bali’s unique energy flow.

Spaces Shaped by Tradition and Social Bonds

A Balinese home is designed to support and enhance the traditional communal lifestyle, where respect for elders and the extended family structure is fundamental.

Each family compound, or pekarangan, is thoughtfully organized to accommodate multiple generations living together harmoniously. Key pavilions are arranged with purpose: main sleeping pavilion, often reserved for the head of the family or respected elders, reinforces the cultural respect for seniority. Other pavilions serve different functions – for receiving guests or for ceremonies –creating spaces that encourage family gatherings, rituals, and daily interaction, fostering a strong sense of togetherness and community.

The structure and layout of these compounds also ensure that family members can support one another in practical ways. Kitchens and shared open areas like the natah (central courtyard) are designed to be accessible to all, making it easy for family members to cook, work, and gather together. The communal design of the compound supports both privacy and interconnectedness, with shared spaces for socializing and individual pavilions for personal needs.

This traditional architecture creates a lifestyle where caring for each other, especially elders, is woven into daily routines, fostering a natural flow of support, respect, and unity that defines Balinese family life.

Layout and Key Structures in a Traditional Balinese Home

A traditional Balinese home is organized into a walled compound with various pavilions, each designed for specific purposes that reflect the family’s social roles and cultural values. These structures serve practical, communal, and spiritual needs, with layout decisions guided by Balinese principles of harmony and respect for sacred directions.

A traditional home is organized into a walled compound with various pavilions, each designed for specific purposes that reflect the family’s social roles and cultural values. These structures serve practical, communal, and spiritual needs, with layout decisions guided by Balinese principles of harmony and respect for sacred directions.

Layout and Key Structures in a Traditional Balinese Home

These are the 7 main elements of a traditional Balinese home

- Paon (Kitchen): Located in the southeastern part of the compound, the kitchen is a simple, functional area where family meals are prepared. It symbolizes the home’s source of nourishment.

- Bale Sekenam (Family Pavilion and Work Area): Typically located near the central courtyard, this open pavilion serves as a place for family members to rest, work, and gather, embodying the communal aspect of Balinese life.

- Bale Sikepat (Gentlemen’s Pavilion and Work Area): This pavilion is traditionally designated for male family members, providing space for work and social gatherings within the family.

- Uma Meten (Pavilion for Single Women): Reserved for unmarried women in the household, the Uma Meten is a private space, reinforcing traditional social roles within the compound.

- Bale Tiang Sanga (Parents’ Pavilion): Occupying a revered position in the compound, this pavilion is reserved for the head of the family and elders, symbolizing respect for family hierarchy and heritage.

- Lumbung (Food Storage Granary): Elevated to protect against bugs, rats and other pests, the lumbung stores rice and other staple foods, reflecting the family’s prosperity and connection to the agricultural heritage of Bali.

- Pamerajan (Family Temple): Located in the most sacred northeast corner of the compound, the family temple is dedicated to ancestor worship and daily offerings. It serves as the spiritual center of the home and is essential in maintaining the family’s connection to their ancestors and the divine.

Some pavilions, or bale, are semi-open structures that provide shelter but allow airflow, perfectly suited to Bali’s warm, humid climate.

The Home reflects the social status, caste and wealth of a family

In traditional Balinese architecture, the number and type of structures in a family compound can vary significantly depending on factors such as family size, social status, and financial means. While wealthier families or those of higher caste (such as the Brahmana or Ksatria) might have more pavilions, a smaller or less affluent family would likely build a simplified version of the compound.

3 Minimal Structures and Essential Layout

At its core, a traditional Balinese compound typically includes three essential elements and families will build these 3 structures, even with very little means

- Family Temple (Pamerajan): This is considered indispensable in any Balinese home, regardless of financial status. It occupies the most sacred corner of the compound (typically the northeast, kaja kangin direction) and is essential for daily offerings and ancestor worship.

- Sleeping Pavilion (Bale): Most compounds will have at least one bale, then serving multiple purposes if other pavilions are unaffordable. This bale functions as the main living and sleeping space for family members, with the layout modified to accommodate the family’s needs.

- Kitchen (Paon): The kitchen is another essential element. It serves not only as a cooking space but also as a symbol of the family’s ability to nourish and sustain itself.

The decision to add other structures depends on the family’s resources and social responsibilities. The undagi (Balinese architect) and priests advise on the ideal layout for balancing the compound’s spiritual harmony while respecting these practical constraints. Financial means, family needs, and local customs ultimately define the layout and complexity of each Balinese home, making each one unique yet culturally coherent.

In any case, whatever the financial means of a Balinese family, these spaces are constructed with reverence for the divine, usually accompanied by ceremonies, including the melaspas purification rite, which consecrates the house as a living entity.

Building Material & Artwork

Balinese traditional architecture uses natural, locally-sourced materials, with each choice carrying cultural meaning and purpose. Structures are often built from volcanic stone, bamboo, teak, coconut wood, and clay bricks. These materials not only reflect Bali’s lush, natural environment but also serve practical purposes: bamboo and wood create open, airy spaces suited to the tropical climate, while volcanic stone and clay bricks offer sturdy bases for more enclosed structures.

Carvings and decorative elements, seen on doors, gateways, and pillars, are more than just artistic touches. Each carving often depicts mythological stories, symbols, or protective spirits. For example, the Kala head—a fierce, protective face carved above doorways and gates—represents a guardian spirit, meant to keep negative energies away. Additionally, floral and animal motifs, like lotuses or naga (mythical serpents), are common and symbolize purity, balance, and connection to nature. Each piece is a reflection of Bali’s rich spiritual and cultural heritage, imbuing spaces with layers of meaning that resonate with Balinese beliefs about harmony and protection.